Inami woodcarving is one of Japan’s most renowned traditional crafts, originating in Nanto City, Toyama Prefecture. The town, home to over one hundred professional woodcarvers, has sustained this art form for more than 250 years through a continuous master–apprentice tradition.

Origins and History

Inami’s story begins in 1390 with the founding of Zuisenji

Temple, a branch of Kyoto’s Honganji Temple. The temple’s

construction attracted skilled carpenters, and Inami

flourished as a centerof craftsmanship.

In 1762, a fire

destroyed Zuisenji, and a sculptor from Kyoto named Maekawa

Sanshirō was invited to assist in its reconstruction. After

teaching local temple carpenters his techniques, Inami

gradually evolved into a town of specialized woodcarvers,

establishing the foundation of its distinct style.

Sanshiro’s dragon carved on the temple gate at that time

still stands today as a symbol of the craft’s beginnings.

During

the Meiji period (early 20th century), Inami artisans

expanded beyond temple ornamentation to produce ranma —

carved transom panels used in traditional Japanese

homes.This innovation brought Inami woodcarving into daily

life and led to a period of remarkable growth. By the

postwar era, more than 300 artisans were active, making

Inami Japan’s largest woodcarving center.

Techniques and Characteristics

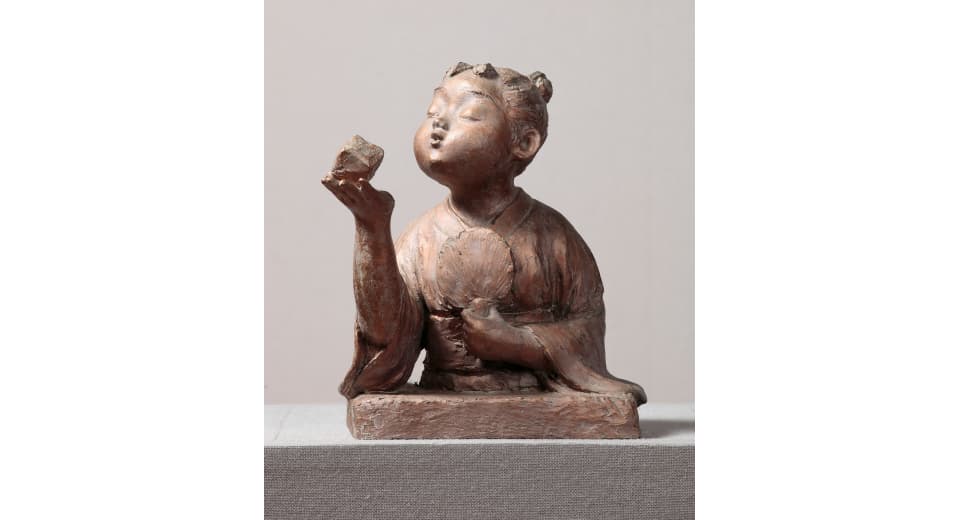

Inami woodcarving is defined by its creation from a single block of wood, an art of subtraction that reveals form

through continuous carving. Each piece is executed entirely

by hand; carvers never use sandpaper. Every surface is

finished with chisels alone, requiring exceptional precision

and control. A single work may involve more than two hundred

chisels of different shapes and sizes.

Camphor wood is the primary material, valued for its

flexibility and durability. The process begins with a

detailed sketch (shitae), followed by rough carving,

intermediate carving, and final finishing. The composition

must remain structurally connected to its frame, with every

line and curve contributing to harmony and balance.

Apprenticeship and Transmission

The foundation of Inami’s longevity lies in its traditional

apprenticeship system, which lasts a minimum of five years.

Apprentices begin by cleaning the workshop and maintaining

tools, spending months learning to sharpen chisels by hand

before ever carving wood. Through years of observation and

practice, they internalize the master’s rhythm and

technique, gradually progressing to independent work.

Today, while many apprentices no longer live with their

masters, the principles remain unchanged. Within the Inami

Woodcarving Cooperative, artisans collaborate, train new

generations, and take part in restoration and cultural

exchange projects.

Inami Today

Although domestic demand for traditional ranma has declined

due to changes in architecture, Inami’s craftsmen continue

to adapt. Many now apply their skills to contemporary

design, furniture, and architectural commissions, while also

restoring cultural landmarks such as Nagoya Castle and Shuri

Castle.

Yet this shift marks a critical turning point. As demand for

traditional work has fallen, so too has the number of

masters able to sustain enough apprentices to cultivate a

future generation of skilled carvers. Most of Inami’s master

craftsmen are now over the age of sixty, and without new

opportunities and global awareness, the transmission of

these centuries-honed skills faces the risk of disappearing

within a single generation.

Through its collaboration with Poiesis, Inami’s artisans are

expanding their work to new motifs and symbolisms for

clients around the world. Their craftsmanship continues to

evolve while remaining grounded in centuries of discipline

and precision.

Inami woodcarvers take pride in their mastery: “If it is

wood, we can carve anything.”